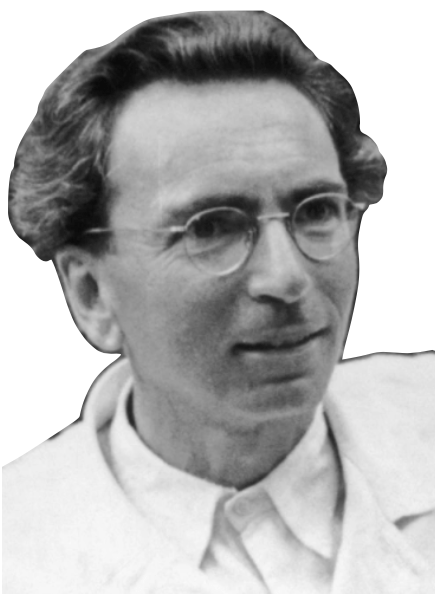

In 1942 Vienna, Viktor Frankl was a respected psychiatrist with a growing practice, a nearly complete manuscript, and a wife named Tilly whose laugh could fill a room and brighten the darkest days. He had a visa to escape to America, but his elderly parents couldn’t come—so he stayed. Within months, the Nazis came for them all. Theresienstadt. Then Auschwitz. Then Dachau. The manuscript he had sewn into his coat was torn away within hours. His name erased. His number: 119104.

But what the guards didn’t understand was this: you can take a man’s manuscript, his name, his possessions—but not what he knows. Frankl knew something about the human mind that would change psychology forever. In the camps, men didn’t just die from starvation or disease; they died from giving up. When a prisoner lost his reason to live—his why—his body followed soon after. But those who held onto meaning—a promise to keep, a family to find, a purpose unfinished—found strength to endure.

Frankl began a quiet experiment in the barracks. He couldn’t offer food or freedom, but he whispered to the hopeless: “Who is waiting for you?” “What work is left unfinished?” “What would you tell your son about surviving this?” He helped men remember their purpose. One thought of his daughter and survived to find her. Another recalled a scientific problem and lived to solve it. Frankl himself survived by mentally reconstructing his lost manuscript, line by line, in the darkness.

When liberation came in April 1945, Viktor weighed only 85 pounds. His wife, mother, and brother were gone. Everything he loved—gone. Yet, instead of collapsing, he began writing again. In just nine days, he recreated the manuscript from memory, now filled with something new: proof. He called his theory Logotherapy—therapy through meaning—and showed that humans can survive almost anything if they have a reason to live.

Published in 1946 as “Man’s Search for Meaning,” the book was first rejected as too grim. But slowly it spread. Therapists wept. Prisoners found hope. Ordinary people facing illness, grief, or loss discovered that their pain could still hold purpose. The book has sold over 16 million copies, translated into more than 50 languages, and remains one of the most influential works ever written about resilience and the human spirit.

Because Viktor Frankl proved what the Nazis could not destroy: that even when everything is taken—freedom, family, food, future—one final freedom remains: the freedom to choose what it all means. His words still guide those in despair: “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.” Prisoner 119104 didn’t just survive. He turned suffering into healing—and taught the world that meaning is the one thing no one can ever take away.